Two Great War Plays: ‘The Porter of Hell’ and ‘The Toast’. By Susan Hinchsliffe

As part of the Great War Theatre project I’ve recently been transcribing a number of plays written and first performed during the First World War. Sitting in the British Library working on the latest play, The Porter of Hell, licensed in 1918 although set in 1914, I was struck by now different in tone it was from another text I’d recently typed up, The Toast, actually written in 1914.

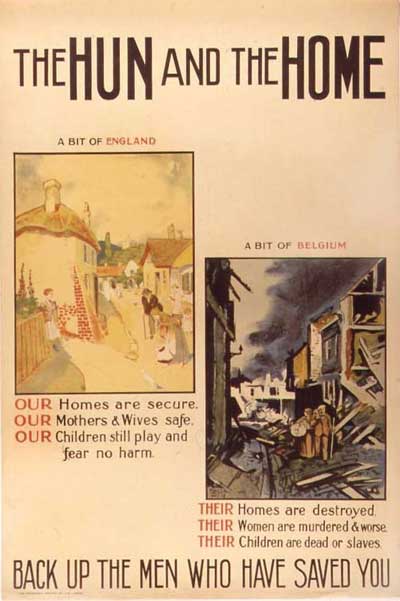

The plays are similar in subject matter. Both are set on the Western Front after the German invasion at the beginning of the war. Both portray the Germans as bestial. Both have women who take decisive action. But what a contrast they present!

The Toast

The Toast, written by actor Frank Bertram, was licensed for performance at the Savoy Theatre in October 1914. His brother Arthur was a manager of the theatre. At the start of the play a wounded British officer, Charles Vivian, is being sheltered from the enemy by a young French woman, Marie Roche. He’s a Bertie Wooster-like character, complete with eye-glass and constantly exclaiming, “Oh! I say!”. He apologises to her for being such a “beastly nuisance” and tells her that it’s “awfully good” of her to hide him from that “bounder” of a German officer (p2). Vivian is the stiff-upper lipped English gentleman and his instinct is to protect his female saviour and offer her shelter with some friends of his.

Enter Prussian soldier Lieutenant Koenig (German for ‘king’, almost a synonym for Kaiser), whom Marie has already described as “the most cruel and cold-blooded devil in the German Army” (p4). Finding that Marie has hidden a British soldier, Koenig threatens her with the ‘fate worse than death’ and spares us no detail as to the punishment he has in store. The Examiner of Plays commented:

There is no harm just now in this dramatized newspaper story from the front, except in the brutal coarseness of the Prussian’s threats to the young woman:

“I’ll whip you first and dishonour you afterwards”, and “Off with your clothes, every stich of them”, which should be omitted.

German atrocities reported in the newspapers early in the war are mentioned in the play: lack of respect for the Red Cross and the White Flag; the burning of churches and hospitals; and brutality towards women, children and prisoners of war. But the overall tone of the play is light. Charles Vivian brings humour to the piece and Koenig has something of the pantomime villain about him. He wants the British soldier to say, “Hoch der Kaiser!” as he executes him. Vivian is characteristically dismissive, replying “You can cut that!” But Marie gets in first and shoots the German, allowing Vivian in the nick of time to change his toast to “God Save the King”, the original title of the play.

Unfortunately I have not been able to find out if this play was ever performed: the Savoy Theatre has nothing in its archives about the play and I haven’t managed to track down any reviews of it elsewhere.

The Porter of Hell (A Drama of 1914)

The Porter of Hell (A Drama of 1914) presents us with a very different view of this early period of the war. It doesn’t hesitate to spare us the shocking facts of what it must have been really like to suffer at the hands of the invading army. Written by Lt.Col. W. P. Drury of the Royal Marines, it was licensed for performance towards the end of the war. Drury already had a long military career behind him and worked in Intelligence in Plymouth during the war. Surely with this first-hand knowledge of war his play would be more realistic than Frank Bertram’s.

There is no humour in his play at all. From the start we are presented with the destruction wrought by the invading German army on the family chateau of the Comtesse Gabrielle de Beaucourt. Reflected in the shattered windows is the lurid red light of the nearby burning buildings. “Shall I ever see any other colour again?” asks the Comtesse (p2). The stage directions (p1) specify the rumble of distant guns and incidental music to suggest “the desolation of despair and terror of a war of invasion”. The weariness and horror of the war, which for the contemporary audience has already gone on for four years by this stage, obliterate any sense of optimism, even though the scene depicted is in the early days of the conflict.

The Comtesse’s elderly mother-in-law, her mind unhinged by what she has witnessed, remembers the pre-war Germans as delightful friends and a cultured people. But, as in The Toast, we learn of German atrocities perpetrated on children and wounded prisoners. Now, however, they are more immediate: the Comtesse has seen her own children mutilated and knows the Germans are starving her husband, currently their prisoner-of-war (p3). There is no Charles Vivian here to play the dashing English gent and save the Comtesse from the dastardly Hun.

The Comtesse’s recent experiences have desensitised and brutalised her – “made me hateful to myself,” she says (p3). With something of the ‘unsexed’ Lady Macbeth about her, she vows to kill the next German she sees. It is a marked contrast to Marie’s heroic shooting of Koenig in The Toastin order to save the British soldier. Here, the Comtesse’s unremitting misery leads her to turn on a drunken Prussian officer and hammer a nail into his neck. Only afterwards does she discover that he is in fact her husband, recently escaped from an enemy prison camp and disguised in a German uniform.

And what of the German himself – a Prussian again – in this play? The German villain, Major Karl Henkel, the self-styled ‘porter of hell’, is no longer taken from the pages of a melodrama. Silhouetted against the fiery background, he is the devil incarnate. With an ironic veneer of civility, he clicks his heels chivalrously and admits the Germans are good haters. Like Koenig, he sees rape as a suitable punishment for any female enemy. To avoid this ‘fate worse than death’ and now in utter despair, the Comtesse commits suicide over the body of her husband (p 6-7). The heartless Prussian merely shrugs his shoulders and exits.

We were warned at the beginning of this project that there were few dramatic masterpieces awaiting us. But these two plays aren’t without dramatic worth, especially in a historic context. To me that change in tone from the The Toastwith its sense that the war is all a bit of a lark to The Porter of Hell’s vivid portrayal of the horrendous realities of suffering and despair clearly denotes two contrasting contemporary reactions to the Great War, four years apart.