A Researcher’s Tale by Mike Waters

In this blog post, Mike Waters, one of the project’s volunteer researchers, shares his experience – and some of the extensive challenges, as well as unexpected discoveries in tracing long-forgotten plays and playwrights.

I volunteered for the Great War Theatre project after spending many years researching my family history and finding several forebears who died in the Great War. I’ve also researched some quite different bits of theatre history and thought my various interests would fit together well. I can access the British Library’s northern outpost near York so getting hold of books and print copies of newspapers would be easy. Oh, and my wife wanted me to have something new to occupy me!

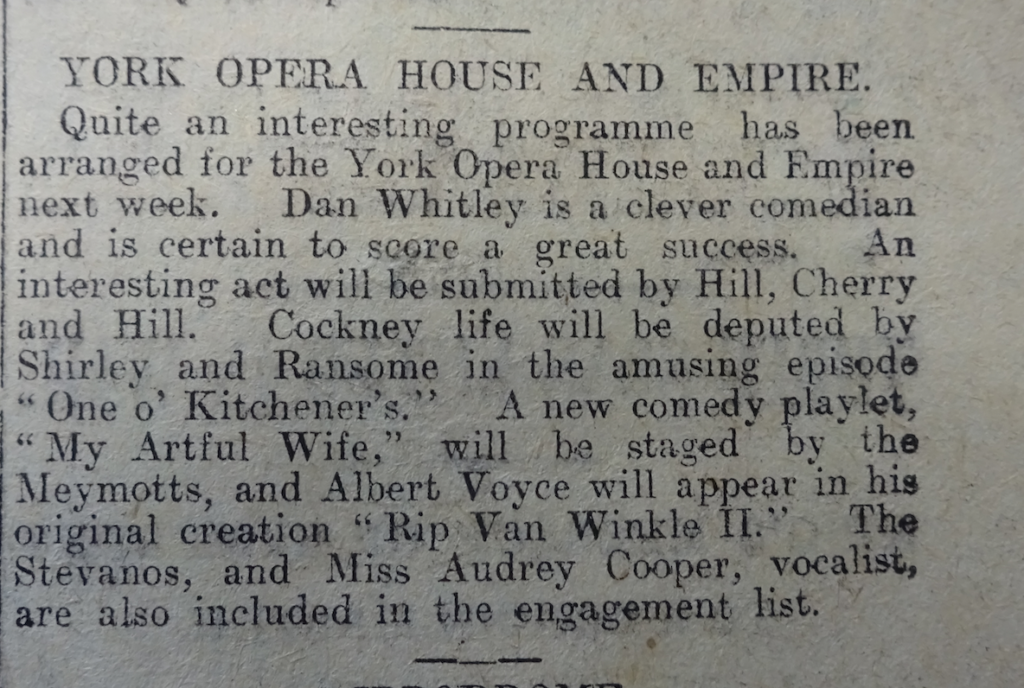

So, I thought, that all looks straightforward. Wrong! My first play was One O’ Kitchener’s, a recruiting sketch, written and played by cockney comedians Chas Hickman and May Ransome, that was first performed in December 1914. I found records of performances but could not identify or trace Hickman or Ransome anywhere. And the sketch was performed nine months before the official first date in the Lord Chamberlain’s papers so if I had worked forwards from this I would have missed a lot.

But at least that sketch was performed, unlike – apparently – two others that came my way. A Theatrical Marriage was submitted anonymously for performance in Leeds in May 1917, but it wasn’t performed then or at any other time, at the theatre in question or at any other. But a play of the same name was apparently being written in December 1915 by the former actress Cissie Grahame; however, there’s no record of it being submitted to the Lord Chamberlain’s Office or performed. Were they the same play? I just don’t know. And one E. L. Prentice, of whom I could find no trace, wrote Milady Does Her Bit for a charity show in London in April 1918, in aid of the Nation’s Fund for Nurses, but the event was cancelled at the last minute and the play seems to have died with it.

Both those plays were licensed very late in the day: A Theatrical Marriage the day before its proposed first performance and Milady Does Her Bit only four days in advance. I wonder how common it was for the licence to come through at the last minute, and if producers were prepared to gamble on a play being approved without changes and to put it into rehearsal while waiting for the licence. After all, things might go wrong: The Stage on 2 September 1920 announced that E. Vivian Edmonds was unable to produce his new play, Her Unknown Husband, as announced the previous week, owing to the license not having arrived.

But surely researching plays that were definitely performed and that were written by identifiable authors with discoverable dates of death (for clarifying the copyright position) must be a comparative doddle. Er, not necessarily. Some plays changed their names part way through their stage lives. Bernard Shaw’s Annajanska, The Wild Grand Duchess, first performed in January 1918, became Annajanska, The Bolshevik Empress when it was published the following year, so subsequent performances were recorded under the new, Shavian-paradoxical title. At least that was easy to spot. Dorothy Lloyd Townrow wrote Within Our Gates for performance in May 1916 and it was still being produced under that title in January the following year. But then a ‘new play’ For Motherland was announced, only for reviews to show that it was the same play as Within Our Gates. It continued to hold the stage under its new title into 1918. I’ve no idea why the change was made. More explicable is

’ decision to rename his play Called Up (performed July to late November 1918) as Coming Home (November 1918 onwards), since the replacement title fitted better the concerns of the post-war period. But, like Miss Townrow, he still thought it would be good marketing to call his rebadged show a ‘new production’.

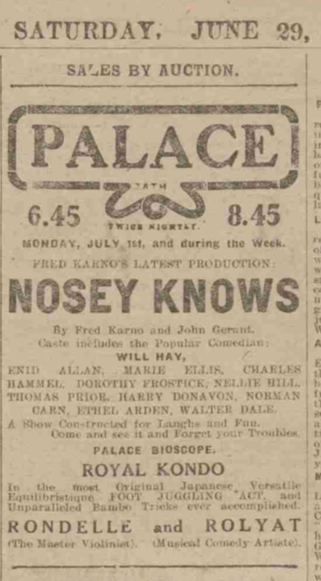

Even if the title stayed the same, the play might not. Nosey Knows was a sketch written by Fred Karno (and others) and first performed by one of Karno’s troupes in October 1917. It was re-licensed for performances in February and July 1918, although the licensing reports do not show why. It may have been the sort of show that was always likely to be added to or subtracted from, since an early review commented, ‘Excellent though it is at present, one readily appreciates that Nosey Knows will develop into something even better’. It is possible that more songs were added in February 1918. But the reason for the July 1918 change is more obvious. Previously Karno had launched the careers of Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel. Now, a few months into the run of Nosey Knows, he brought in Will Hay, who is best known today for the films he made in the 1930s and 1940s, such as Oh, Mr Porter!, Ask A Policeman and Where’s That Fire?. In December 1917 Karno’s show had shared a bill with other turns including Will Hay who, according to the Liverpool Daily Post and Mercury, ‘[made] clever play with the character of a schoolmaster confronted by a sharp-witted and not over-respectful scholar’. This was Will Hay’s celebrated (at the time, anyway) ‘schoolmaster sketch’, in which Thomas Prior had played the schoolboy, something of which can be seen here. Prior also joined the cast of Nosey Knows and he and Will Hay shoehorned some of their material into it, necessitating the July 1918 relicensing. As a bonus I was pleased to find an image of a photograph, displayed on the wall of a pub in Ramsgate, of Will Hay as Nosey Parker in this play.

There is a lot of information about the plays in the advertisements that theatre companies placed in newspapers, especially The Stage. If a company was seeking bookings in the future, the addresses where it could be contacted that week and next provide evidence of where a play was being performed. E. Vivian Edmonds sought to show how popular his plays were in advertisements aimed at theatre managers who might have vacant dates in the future that could accommodate his company. He did this by listing previous weeks’ takings. In the case of Coming Home, for example: ‘Last week Mansfield in spite of epidemic and all soldiers in by 8.30 £364 8s 9d’; ‘Last week, Hippo., Nuneaton, all records broken for drama, £387 15s 4d. Saturday night alone 2,850 people paid for admission’; ‘Last four consecutive weeks: – Grand, Luton £300 1s 8d (without tax); Grand, Brighton £347 19s 6d (without tax); Elephant and Castle £517 1s (without tax); Palace, Bordesley £403 6s 4d (without tax)’; and ‘Last week Opera House, St. Helens, all records broken for Holy Week (the worst week of the year at St. Helens) £458 19s 9d (with tax), £353 11s 10d (without tax) in five nights’. To put the figures into context would require knowledge of theatre capacities, ticket prices and takings of comparable productions at the same venue around the same time. But Edmonds must have thought that his readers would share his understanding of how good the figures were.

On a personal note, I was delighted to get in touch, through the Ancestry website, with the great niece of Edmonds’ first wife. She told me his real first names (Edward Henry John) which made it possible for me to track down details of his birth and death, and I was able in return to add to her knowledge of his theatrical career.

Also of potential interest to theatre historians are the ways in which companies described the plays in their advertisements. Edmonds is adamant in advertisements inserted after November 1918 that Coming Home is ‘not a war play’ but ‘a topical peace (sic) that appeals to everyone’ and ‘a musical play of heart interest and brimful of Comedy’, even though it is set in war time, has British soldiers and a German spy among its leading male characters, includes scenes in a German POW camp and was also advertised as ‘a lesson for those who have taken advantage of the war’. Fred Karno insisted repeatedly that Nosey Knows was ‘not a revue’ but ‘a farcical musical sketch’, which no doubt was an attempt to manage audiences’ expectations but which may also say something about attitudes towards revues in the theatre at that time. Sketches and shorter plays formed part of an evening’s entertainment that also included quite different ‘turns’. Nosey Knows shared the bill with Herbert Cave, ‘the famous English tenor’; Franco, ‘who chalks and talks’; Evelyn Earle, ‘the quick-change girl with a voice’; and Henri Ricardo, ‘novelty comedy conjuror’. Bernard Shaw’s Annajanska appeared alongside Neil Kenyon who provided ‘some excellent studies of Scottish humour’; Vesta Tilley ‘in a new song scena, “London in France”’; and ‘Mr. Mark Hambourg, a circus item, and a touch of ballet from Lydia Kyasht’. Something for everybody, perhaps.

Other aspects of the plays’ performances give an insight into the atmosphere of the times. In June 1918 Nosey Knows was performed for wounded soldiers at the War Hospital, Stoke-on-Trent: ‘The members of Fred Karno’s company … presented the piece in its entirety, and the performance was keenly appreciated’.

Performances of the same play at the Hippodrome, Coventry in the following month were accompanied by ‘special war films’.

And I noticed an advertisement for Submarine F7 (not a play I have researched) in York in August 1915 which announced that each performance would be attended by Corporal F. W. Holmes V.C., M.M.: ‘Corporal Holmes is the only living soldier who is the proud wearer of both crosses, the M.M. being in France what the V.C. stands for in England’. Frederick Holmes from Bermondsey, London, then a Lance Corporal in the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, had been decorated for an action on 26 August 1914 at Le Cateau on the Western Front.

I have found very little information about the audiences’ responses apart from generalised statements that they enjoyed a play and enthusiastically applauded it. Coming Home was described as ‘a play for the soldiers. A play for mothers. A play for sweethearts who have prayed and longed for those two words – Coming Home’, and that view of the prospective audience is unsurprisingly confirmed by an earlier review of Called Up which noted that ‘it … appeals, perhaps particularly, to women with husbands, sons or sweethearts at the war, and who necessarily form the larger part of entertainment patrons’.

Some of the plays soon ceased to be relevant. The recruiting sketch One O’ Kitchener’s remained popular until around the time of the introduction of conscription in 1916; and Nosey Knows was last performed in December 1918. Others lived on. Coming Home was still being performed in November 1922; and Annajanska was revived professionally in 1930, 1939 and 1951 and was also performed by amateur groups: the Burnley Drama Guild in 1931, an Edinburgh group in 1936 and the Thurso Players in 1950.

Of course, whatever we find out about these plays is necessarily a snapshot of what was recorded in newspapers. New pages are being added all the time to the online resources and it is possible to search in the British Newspaper Archive (BNI) for pages that have been added since a specific date. At the risk of creating more work for ourselves, perhaps we ought, before the project is signed off, to look to see if there is any further information in newspapers recently added to the BNI.