Horror on the London Stage: The Grand Guignol Season of 1915 by Helen Brooks

We’ve been uncovering an incredible range of different war-themed plays as part of the Great War Theatre project but one of the discoveries which has surprised me the most is the season of French Grand Guignol plays which were performed in London in the summer of 1915. Initially I came across these through finding a couple of them being licensed by the Lord Chamberlain (the official responsible for licensing plays until 1968). However with a bit of investigation using the British Newspaper Archive I soon realised that rather than just being a couple of plays, there was in fact an entire season.

The season ran between 14 June and 21 August 1915 and began at the Coronet Theatre, on Notting Hill Gate, before then transferring to the Garrick Theatre in the West End from 19 July. Over the course of the season the Parisian company gave 73 performances of 26 plays (with a further 5 plays being performed by an English-speaking company at the Garrick). Audiences coming to see the plays would already have been familiar with the Grand Guignol. Since the turn of the century, at its theatre in Paris, the Grand Guignol company had been presenting audiences with an evening’s (or matinee) entertainment made up of a series of short plays (usually 4 or 5) mixing comedy with horror. It was a formula known as the ’hot and cold shower’, meaning that audiences would be catapulted between the extremes of affective experience: laughing one minute and screaming (or fainting from fear, as some at the Paris Grand Guignol apparently did) the next.

At the start of the London season it seems that there was some uncertainty about how the horror plays would go down with London audiences, and only one horror piece (La Baiser dans la Nuit by Maurice Level) was included, alongside three comedies. With La Baiser dans la Nuit proving an immediate hit however it was kept in the repertoire for the following week (the standard formula was that each week the plays being performed would change). By the end of the season horror plays seem to have been so popular that they had overtaken comedies in the repertoire: the final week at the Garrick (16-21 August) was made up of 3 horror pieces and only one comedy.

The popularity of these horror pieces with London audiences however seems to have caused some confusion for contemporary commentators. Why, they wondered, would audiences want to witness fictional horrors when real life had far surpassed them? George Street, one of the Examiners of Plays, whose job was to read plays and say whether they could be performed or not (or whether they needed censoring) certainly felt this way. He made the following comments when he was licensing the horror piece Sous La Lumière Rouge for the Coronet Theatre:

‘This is another horrible play, and it is almost incredible that in such dreadful times as these there can be any demand for artificial horrors […] it is only with doubt and extreme reluctance that it is recommended for License’ (22 June 1915, British Library, LCP 1915/17)

Reflecting on the season when it ended in August, The Tatler concluded:

‘[It could] only be curiosity and a certain craving for the morbidly horrible which can turn a season of such plays into a success at a time when the world is already drenched in blood sufficiently, and the blood, alas! is real’ (The Tatler, Wednesday 25 August 1915).

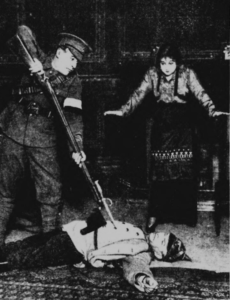

Rather than seeing the popularity of these plays as happening in spite of the war however, I think their popularity was (at least partly) as a result of the war. As Joseph Grixti has argued, horror can be ‘a safely distanced and stylised means of making sense of and coming to terms with phenomena and potentialities of experience which under normal […] conditions would be found too threatening and disturbing’ (Grixti, 1989, 164). From this perspective, during wartime fictional horror can be a ‘safe’ means of exploring the fears and anxieties people had. We see this happening in the Grand Guignol season of 1915 with plays like La Baiser dans la Nuit which features a blinded and facially ‘disfigured’ man being transformed physically and emotionally by his ‘deformity’ and Sous La Lumière Rouge, which deals with fears of being buried alive. Both plays had both been written before the war, but now, in the context of the war, they took on new meanings. By this point in the war, men were already returning with severe facial wounds, and experiencing a mixture of pity and disgust both from family and even those treating them. Meanwhile at the Front, others were being buried alive by shells. In this context then the Grand Guignol offered a fictional space in which real wartime anxieties could be raised, faced head on and explored. It is hardly surprising then that it was such a success.

The ideas explored here were first presented at the International Symposium ‘Dramaturgies of War: Institutional Dramaturgy, Politics, and Conflict in the 19th and 20th Centuries’ at the Goethe-Institut, Glasgow on 26 January 2018.

- Joseph Grixti, Terrors of Uncertainty: The Cultural Contexts of Horror Fiction (London and New York: Routledge, 1989)